hoist the sails.

Following the ESA tender and with support from Delft University of Technology and Inholland University of Applied Sciences, Demcon launched a research project to develop a mechanism for new satellites to deorbit themselves. The first decision the engineers had to make was whether it should be an active or passive system. Active braking, for example, via a separate thruster, sounds logical, but comes with challenges. ‘If you are a little off, a thruster can cause a satellite to spin’, explains Van de Laar. ‘Then you no longer know whether you are pushing it down or accidentally propelling it up.’ Furthermore, there is a human problem: as long as the same fuel or energy can also extend the mission, an operator will be inclined to opt for those extra months of production instead of timely deorbiting. Therefore, Demcon opted for a passive brake: a deployable sail that increases the drag and causes a satellite to lose its potential energy more quickly.

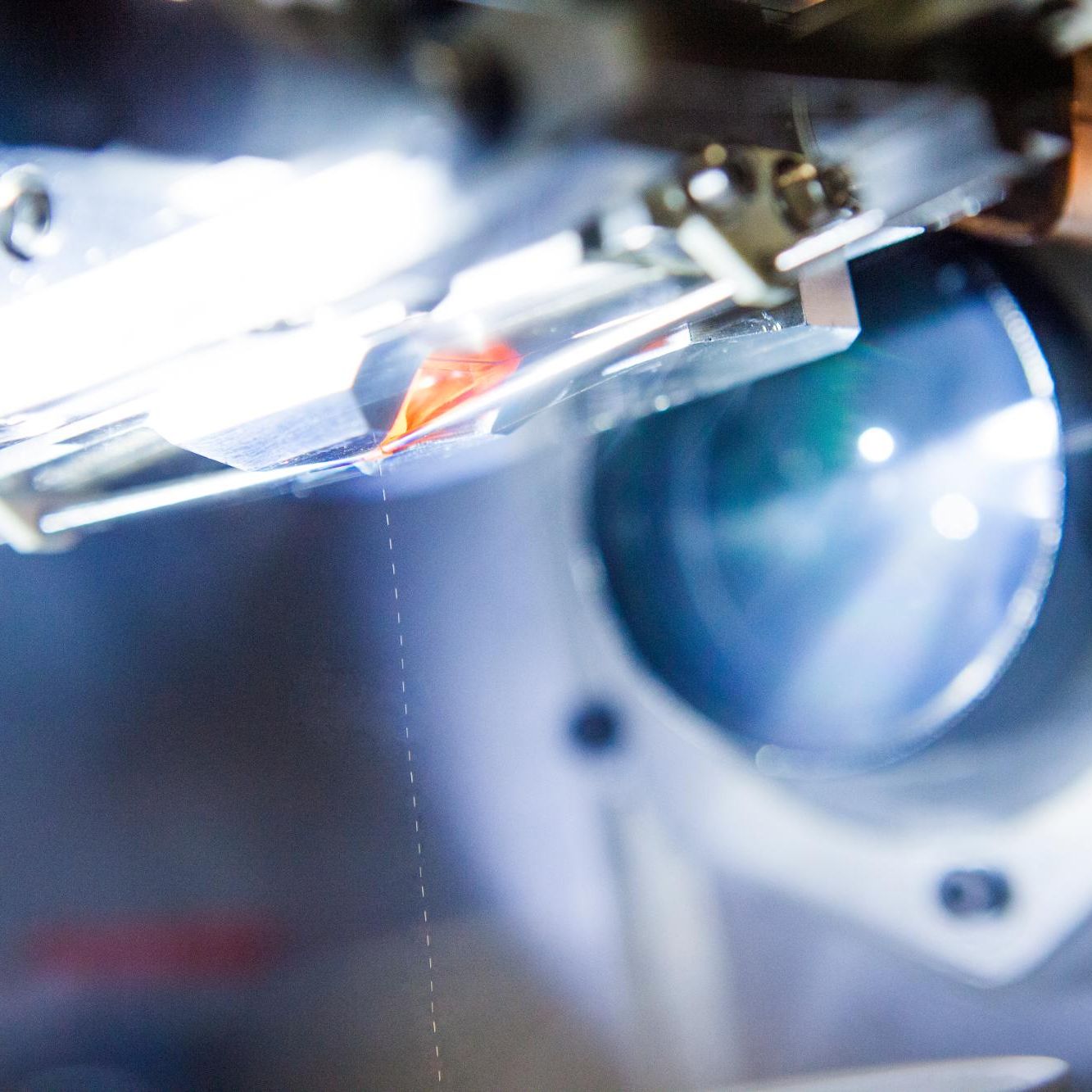

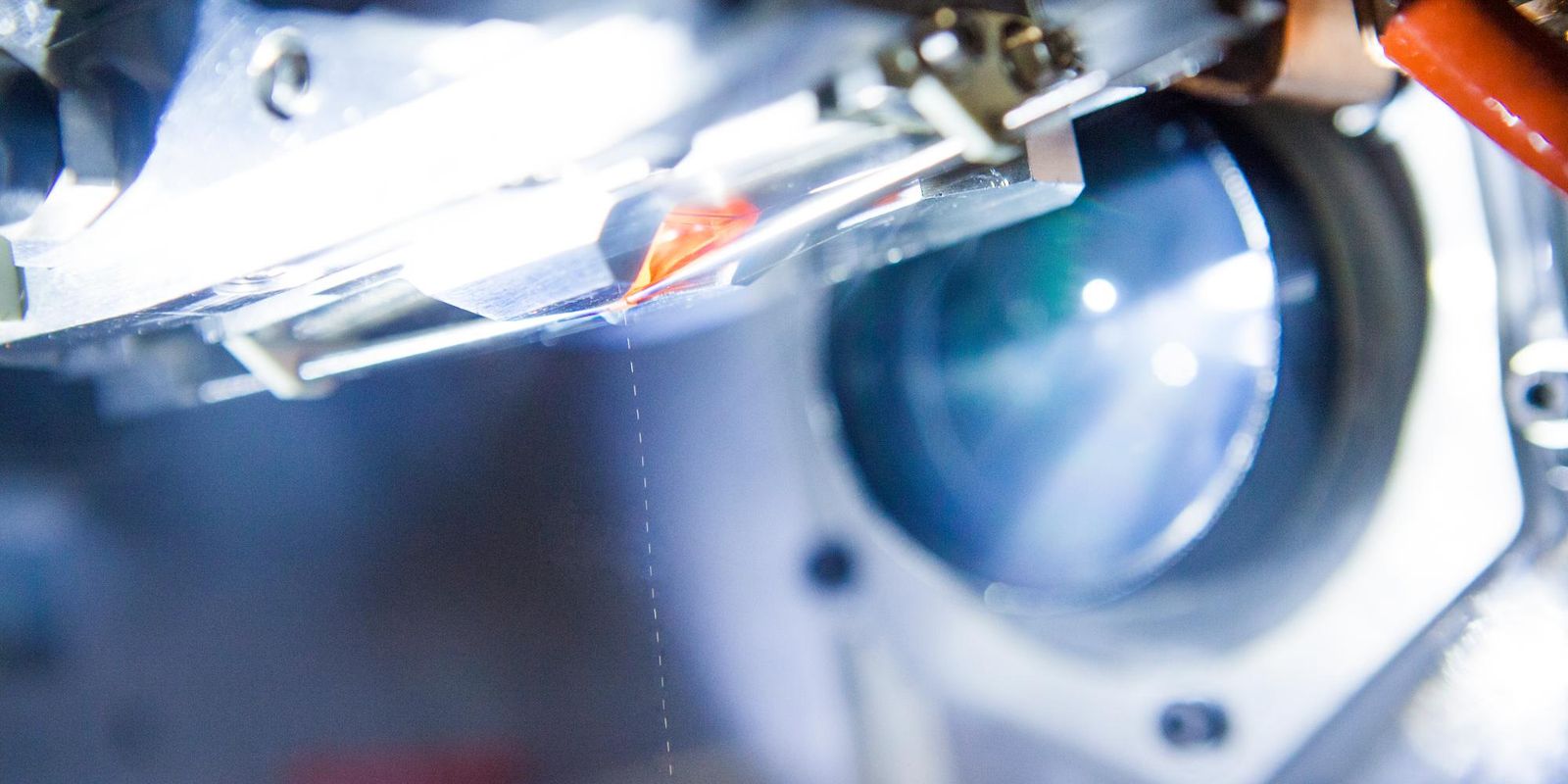

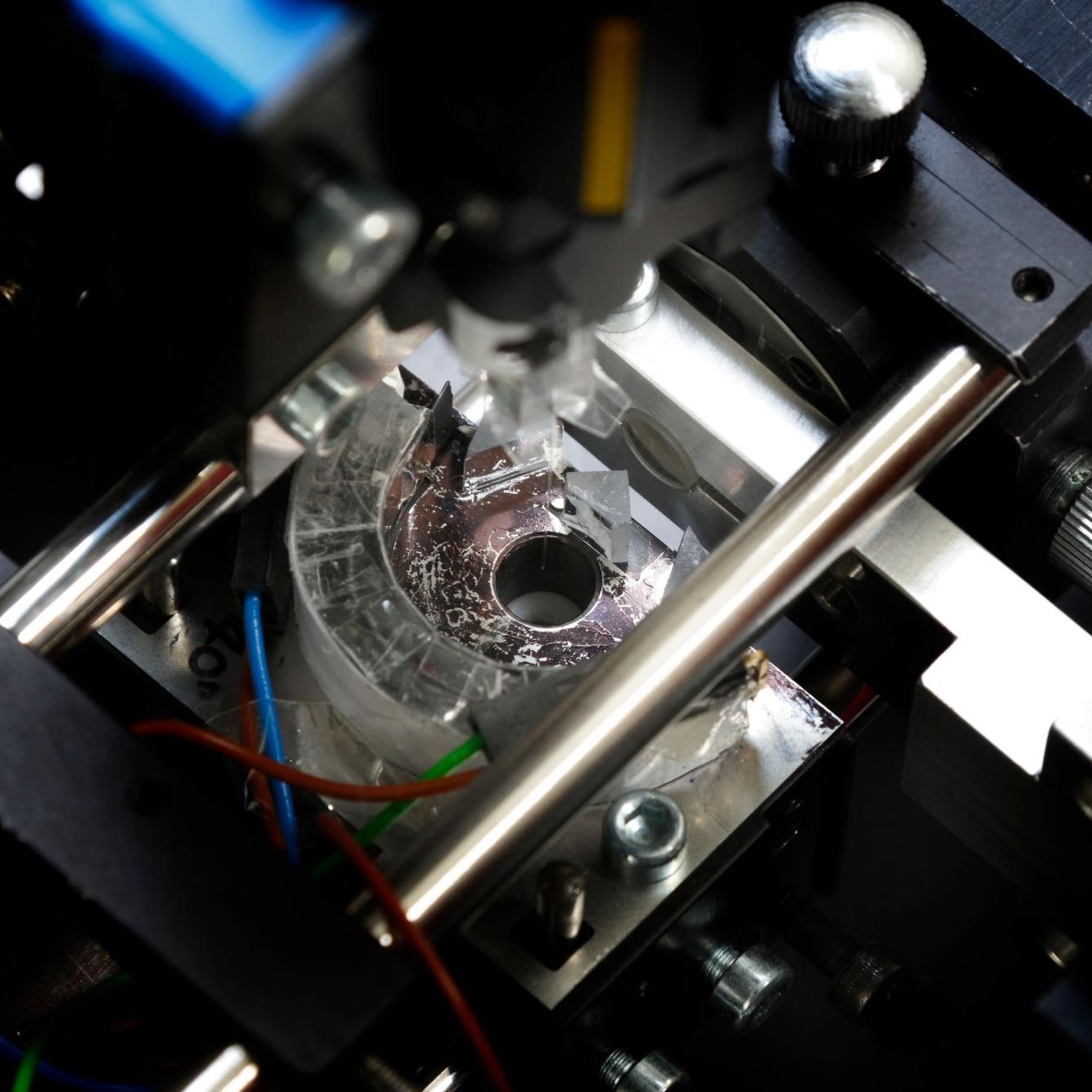

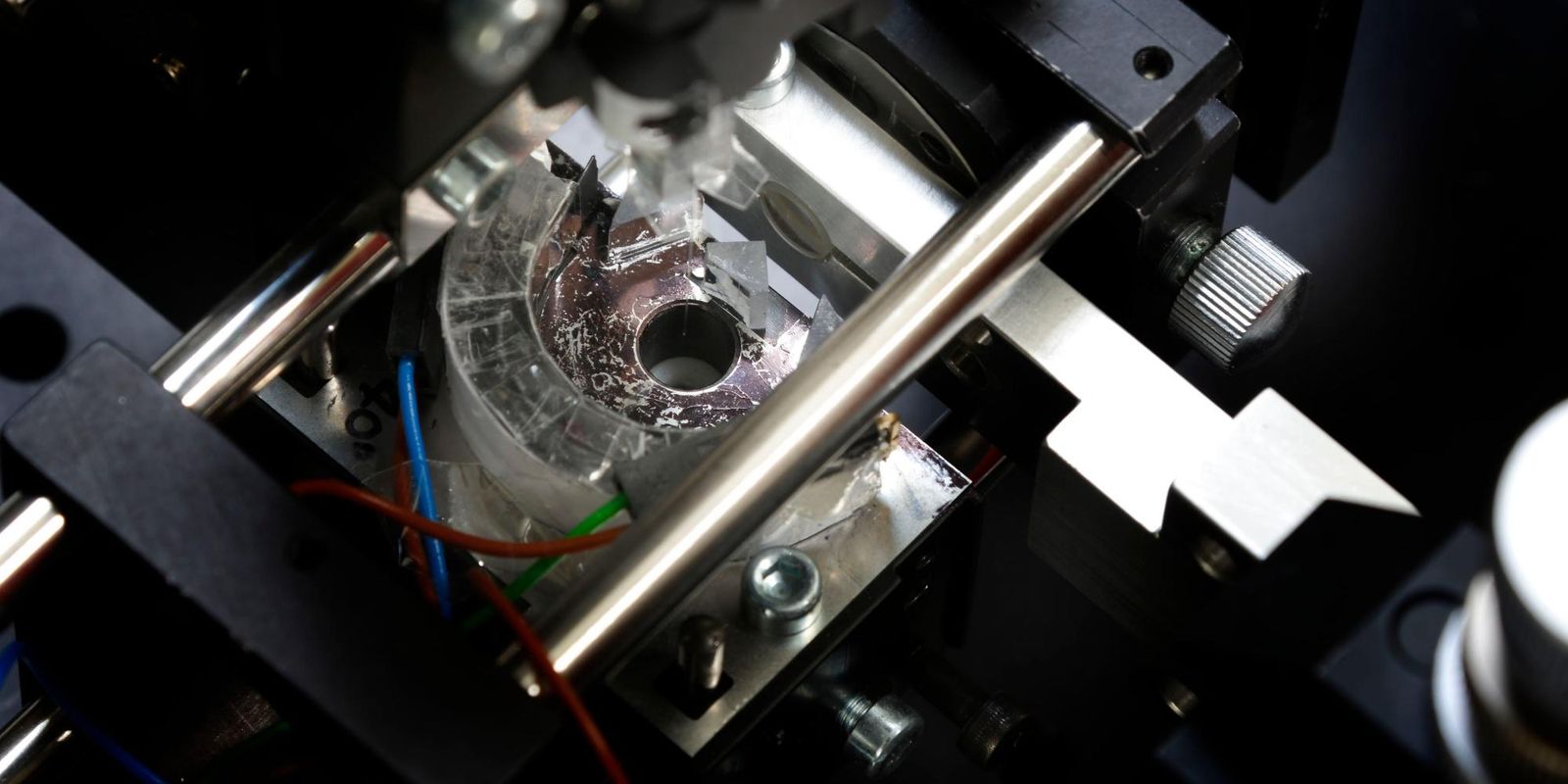

The result of all investigations is an inflatable drag sail system. The 1U cube (10 by 10 by 10 centimeters) houses a folded sail with four flexible booms rolled up like party rolling tongues. An integrated cool gas generator supplies the gas to fill these booms, causing the sail to extend into a square umbrella behind the satellite. ‘Only a small amount of tension is needed to push the folds out of the booms and give them sufficient stiffness. After that, the system can be as leaky as a sieve, because the drag forces are so small, at most a few millinewtons, that the sail retains its shape almost on its own’, says Van de Laar. ‘Only when the system is approaching the atmosphere could a sail with a leaky boom fail. But at that point, it doesn’t really matter anymore, because the end is already in sight.’

Demcon engineers focus on high density: maximum sail area in the smallest possible volume, within a maximum of 1 kg. The goal is to integrate more sail area into the same volume as the mechanical ‘tape measure’ constructions of its competitors. ‘The mass involved in deploying our sail is definitely much smaller than in those mechanical solutions’, says Van de Laar. That is important, because even though it is cheaper to launch a satellite these days, every gram still counts.

simple and robust.

The sail itself is made of conventional space material: a flexible, tear-resistant aluminum foil similar to thermal blankets. Demcon’s rule of thumb is that approximately 50 square centimeters of sail per kilogram of satellite mass is sufficient to reduce the natural deorbit time to about a fifth.